An

instructor of theater criticism once told his students,

"Be careful when critiquing plays that concern war.

It's difficult to be objective." The implication was

that it would be wrong to let emotion, rather than

"professional training," dictate the response.

An

instructor of theater criticism once told his students,

"Be careful when critiquing plays that concern war.

It's difficult to be objective." The implication was

that it would be wrong to let emotion, rather than

"professional training," dictate the response.The jury is still out on his advice, but as far as the current Salt Lake Acting Company production is concerned, emotion is the healthiest way to go.

Playwright Emily Mann wasn't interested in being objective when a Vietnam veteran came to her during the summer of 1978 and pleaded for her to write his story. She said no. She didn't want to write another war play. She had just done that. But when the veteran's wife came to her and talked about her involvement with violence, the playwright said yes.

Director Molly Fowler wasn't objective when she saw the New York production of Mann's powerful play. She never forgot it or the feelings it triggered. She accepted SLAC's invitation to come home and direct STILL LIFE in an attempt to allow its impact to widen.

And then the actors -- Nancy Borgenicht, James Morrison and Deborah Carlisle -- have refused to be detached from the finely drawn characters that Mann has laid on the table.

Although

Mann wrote the play (from the life stories of three

people who are currently living in Minnesota), it is the

production that adds the dimension, the texture, the

smell to her words. She purposefully designed it in

documentary style -- the actors face front and center as

if they are patients and we are the psychiatrist, or is

it the other way around?

Although

Mann wrote the play (from the life stories of three

people who are currently living in Minnesota), it is the

production that adds the dimension, the texture, the

smell to her words. She purposefully designed it in

documentary style -- the actors face front and center as

if they are patients and we are the psychiatrist, or is

it the other way around?They tell their stories from powder blue director's chairs, after all, it is their "movie." They don't physically touch one another but their gestures are about intimacy and the absence of it in their lives. Their props are their hands, their mouths, their consciences, and only on occasion, their hearts. They are detached human beings, not because they were born that way, but rather because of the violence they have allowed to filter into their souls. Now they are trying to regroup, to find a way to incorporate that knowledge into their existence, and somehow to allow the living to continue.

The wife tells of the murder of her nephew by his mother and, a few sentences later, complains of the flowers that don't grow in her backyard because of the neighbor's messy dog. The veteran's lover rails against the destructive nature of Catholicism and tells how she understands acts of violence. The veteran, seated in the middle, relates how he has beaten his wife and then speaks with pride at her courage in giving birth.

The three actors who present these people do so with a great deal of integrity and compassion. With less intelligent interpretations, the characters could be played as unredemptive outcasts of society.

Carlisle,

a fragile blond with the ability to look dazed and bright

at the same time, gives Cheryl a common-sense appeal that

keeps her from sounding totally neurotic. As the

long-suffering and now pregnant wife, her eyes are

red-rimmed and devoid of feeling. She chews on her lips

frantically throughout the show. She looks as if she has

been through the war herself -- and indeed she has.

Through her performance it doesn't seem unreasonable to

hear a woman talk about how she has been abused, but

won't do anything about it -- how she wants to return to

the way things were, but probably won't, and why she

wants to have babies but not husbands. She has detached

herself, but still she goes on.

Carlisle,

a fragile blond with the ability to look dazed and bright

at the same time, gives Cheryl a common-sense appeal that

keeps her from sounding totally neurotic. As the

long-suffering and now pregnant wife, her eyes are

red-rimmed and devoid of feeling. She chews on her lips

frantically throughout the show. She looks as if she has

been through the war herself -- and indeed she has.

Through her performance it doesn't seem unreasonable to

hear a woman talk about how she has been abused, but

won't do anything about it -- how she wants to return to

the way things were, but probably won't, and why she

wants to have babies but not husbands. She has detached

herself, but still she goes on.Nadine has heard the atrocities that Mark committed and still says he's "the greatest man I've ever known." Borgenicht makes that statement digestible because she presents Nadine as a mature woman who has looked at how she has lived and is no longer interested in passing judgment. She sits in her canvas chair, occasionally lights up a slender, brown cigarette, and talks with a directness that demands belief. The performance is honest, controlled and empathetic.

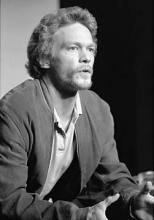

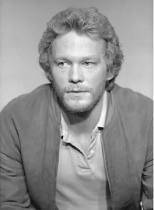

The play is about these two women, but it is James Morrison's intensely captivating presentation of Mark which allows for that dimension. He is powerful and weak, charismatic and repugnant, charming and hateful. He is a victim and a criminal, made so by experiences that he found at once horrifying and thrilling.

His exterior body is nearly motionless throughout the evening, and yet you can feel his pulse with every tortured syllable uttered. His eyes are focused inward, as if he were looking down into his soul every time he spoke, or rather into Mark's soul, or our souls. When at the end he stands and moves closer to the edge, to recite the names of other parts of us, the theater stops breathing. For one moment, there are no detachments, no separations, no judgments -- just emotion and silence. Or to put it another way, a STILL LIFE. Synopsized from reviews by Nancy Melich for Salt Lake Tribune and Joseph Walker for Deseret News

"These are extraordinary performances, nurtured and developed by the actors and director Molly Fowler." Joseph Walker